Beautiful, young, and beguiling Jean Thatcher (Irene Ware) crashes her car, leading to brain damage. The only one with a chance to save her is Dr. Richard Vollin (Bela Lugosi), a Poe-obsessed retired surgeon. Her father, stuffy Judge Thatcher (Samuel S. Hinds) pushes Vollin until he agrees. The operation is a success, and Vollin falls for her, and she has some feeling for him, though she is engaged to Dr. Jerry Holden (Lester Matthews). Her father puts an end to what little chance he had—and it was very little— driving Vollin further into insanity. When escaped murderer Edmond Bateman (Boris Karloff) tries to get Vollin to change his appearance, Vollin deforms him, and uses him as muscle in his plan to torture and kill those between him and the girl.

The Black Cat (1934), combing Karloff, Lugosi, sadism, great sets, and a title—though not story—derived from Edgar Allan Poe was a big hit, so they tried it again, and damn if they didn’t make one twisted and riotous picture. The Raven is outlandish, flamboyant, creepy fun. It’s also pretty shocking for 1935 (the production code was in effect), and scenes like a man tied under the slowly lowering bladed pendulum were used to support the partial ban on horror that was in effect from ’36 to ’38. It can’t live up to The Black Cat’s remarkable art design as few films could, but it beats it in story and sheer wildness. My only complaint is the one I had with The Black Cat; it doesn’t go far enough, but that’s far less of an issue here than there.

While I stated the art direction wasn’t as good, that doesn’t mean it isn’t fabulous. Vollin’s house is a wonder of improbability. It’s properly filled with assorted knick-knacks that can cast shadows, including a stuffed Raven. It also has multiple secret passageways, entire rooms that act as elevators, and a well decked out dungeon with some really nice torture and execution devices. Naturally everyone comes over when there’s a powerful storm.

Karloff is excellent as a killer who’d like to be better, and mostly plays for pathos. Lugosi, however, truly knows what kind of film he’s in and goes full lunatic bombast. This is his film and he looks like he’s having a great old time. His enthusiasm is contagious, and I joined with him wanting to see a few folks get tortured to death. As he quite insanely points out, all this torturing will get torture out of him, making him the sanest man ever. Ummm. Sure. Why not?

This is a bonkers movie and definitely worth your time, particularly at your next horror-themed party.

Successful author William Magee (Gene Raymond) makes a bet that he can finish a novel in 24 hours and heads to a secluded lodge, that’s closed for the winter season, to do so. The timid caretakers meet him there and give him the only key to the place before leaving. He adjourns to a room to write, but is interrupted by a string of mysterious characters, beautiful woman, and criminals (Eric Blore, Grant Mitchell, Henry Travers, and a host of others now mostly forgotten), a majority of whom have a key.

For a property seldom remembered now, Seven Keys To Baldpate certainly was popular in early cinema. And that popularity is why I’m including it. It barely counts as an Old Dark House film, or as a horror one, but it’s too important to the subgenre to skip. The 1913 novel, by Charlie Chan scribe Earl Derr Biggers, was immediately turned into a play be composer George M. Cohan (and no, he didn’t add music). It was very popular, both as an Old Dark House mystery and a parody of such, with the characters purposely one-dimensional representations of what you’d find in less self-aware mystery plays. It was translated into a silent film in 1916. Two more versions followed in 1917 and 1925, with the first sound adaption popping up in 1929. This is the second, and it would be followed by two more, in 1947 and in 1983, the last under the title House of the Long Shadows and including in its cast Vincent Price, Christopher Lee, Peter Cushing and John Carradine.

All of which sets it with The Bat and The Cat & The Canary as a foundational story in the subgenre. It was these movies that were copied over and over for the next twenty years.

This one sets the tone properly with eerie sounds, frightened innkeepers, a raging and surprisingly sinister snowstorm, and talk of ghosts. It follows that with skulking intruders and mysterious guests, but by the time the third key has popped up, the uncanny atmosphere is already dispersing and is long gone before the first act is complete. This doesn’t ruin the picture, but is something of a disappointment for anyone looking for a few thrills. The later appearance of secret passageways and a murder do nothing to restore the creepy feeling.

So we end up with a goofy comedy mystery. It’s quickly paced, with most everyone speaking in quips and ripostes when not simply fulfilling their stereotypes. It’s amusing enough for it’s brief 80 minutes, but it doesn’t have any weight and I can’t imagine anyone caring about either the characters or what happens to them. They are all so preposterous, and the story is ridiculous. Everything about our lead is odd. He doesn’t act like a human. He’s brave to the point of insanity, totally unconcerned with things he should worry about, and is obsessive about the first girl he sees in the area. He’s funny from time-to-time, though less so than the scene stealing hermit and part time ghost (Henry Travers) whose hatred of women is a running gag, but he’s impossible to get invested in. And there’s a reason for that. In the play, everyone acts strangely because no one is who they appear to be. Everyone except the writer is an actor sent to distract him so he losses his bet. But then it turns out even that isn’t true as everything has just been the novel that the author has been typing the whole time.

However, for this version, the meta-narrative was pulled, as was everyone being actors, but their peculiar way of behaving was kept in. That leaves us with everything feeling false and silly with no explanation, and therefore, no point. That doesn’t mean it isn’t enjoyable. The 1929 version starring Richard Dix (one of those major stars of the ‘30s that’s vanished from popular culture) kept the meta-narrative, and it isn’t as entertaining as this one. The characters are false, but I don’t mind spending time with them, and it’s a nicely, if not particularly, artistically shot flick. Call it a diverting curiosity.

Sam Higgins (Gordon Harker) arrives at an isolated Welsh village to take over running the local lighthouse. The villagers are a strange and superstitious lot, believing the lighthouse to be haunted, a belief that is buttressed by the disappearance of the previous lighthouse keeper as well as Tom Evans (Reginald Tate) having just gone mad while in the lighthouse. Not only do the ghosts attack those who trespass on their domain, but they also create a phantom light, thus summoning sailors to their doom. Higgins is approached first by beautiful and bouncy Alice Bright (Binnie Hale), who he mistakes for a prostitute, and then by reporter Jim Pearce (Ian Hunter), both wanting him to take them to the lighthouse. He refuses, and then heads out in a boat with local authorities, including the one stable person in the area, Doctor Carey (Milton Rosnier), who need to check on Evans. The Doctor concludes that Evans is in no shape for the difficult trip off of the island, and so must stay at the lighthouse with Higgans and his two underlings, cheerful Bob Peters (Mickey Brantford) and dour and hulking Claff Owen (Herbert Lomas). Pearce and Bright find their own way to the lighthouse in a small boat, and then are stuck there for the night. What do Pearce and Bright want and who are they really? What drove Evans insane, and are there ghosts? The answers will come before daybreak.

Six people confined to a eerie building on a foggy night, with doors opening on their own and talk of ghosts. Yes, we’re in Old Dark House territory once again, with a lighthouse swapped in for a dilapidated mansion for the second time in 1935. But this British entry doesn’t resemble Hollywood’s lighthouse spooky film Sh! The Octopus, but England’s own The Ghost Train. It was based on the stage play The Haunted Light, which I haven’t read, but assume was either itself based on the play The Ghost Train, or the filmmakers decided to borrow from the film The Ghost Train as much as from the play they were supposed to be using. They both have the same tone, with a lot of humor, focused on a few characters while everyone else plays it mostly straight. They have creepy moments with the newly arriving folks hearing the ghostly tale of the place from a local who is terrified. Both have a significant fraction of the characters not being who they say they are. They have plans by the heroes and villains that don’t stand up to scrutiny. And they have very similar secrets that are revealed in the final act.

This isn’t a comedy as it is often labeled, but fits best in the horror, thriller, and mystery genres. There is humor, but it is soft, not so much gags or big jokes as quirky character moments, and those come mostly from Gordon Harker, He was a stage comedian who got a good deal of work in film playing the third banana comic relief character. Leads were rare for him. Here Ian Hunter takes on the romantic bits, leaving Harker the lighter tones, and he does a nice job of it. As do the rest. It’s a good cast. They are given reasonable dialog to speak and a passable plot to act out, though one that has a few major problems with why people act the way they do. All of which would make this a decent but unremarkable little film. But it has something else. It has Michael Powell.

Powell, once he partnered with Emeric Pressburrger, became one of the greatest directors of all time. He helmed I Know Where I’m Going!, A Matter of Life and Death, The Red Shoes, and what I consider to be one of the top 10 films ever made, Black Narcissus. He had an incredible eye for what worked on camera and was willing to break all the rules. And as subject matter he often touched on the normal person in what he/she considered the normal world stepping into what he/she felt was a more primitive environment, and then finding that “normal” and “primitive” don’t mean what they had seemed to mean (not a view that was big in England as the empire faded). And in 1935, he was a young, though busy filmmaker. As was common at the time in Britain, he learned the craft by working on quota quickies—low budget films made in England that were used to fulfill the requirements that a percentage of all movies be made locally. If theaters wanted the latest blockbuster from the US, they had to show a British picture. Not surprisingly, few of the quota quickies were great art, or even passable art. It took something special to elevate movies where the producers only cared that they existed, not that they were any good. Powell couldn’t make gold from the lead, but he could make silver. And The Phantom Light was a quota quickie.

So many shots in The Phantom Light have the Powell touch. There’s sudden, shock close-ups. There’s winding camera movements. There’s shadows wrapping the frame. Early on, and again when the towns people head for their boat, there’s a documentary texture; Powell used a documentary-type style with some of his early classics. But he is particularly known for his surrealistic tendencies, and those are on full display. By the end, The Phantom Light feels like a dream, one that is terrifying on the edges, but is not a nightmare. And that’s Powell. I find something Lovecraftian about his work: the world is fine here, though perhaps a bit boring, but just beyond here, things get strange, and beyond that are wonders and horrors we cannot conceive. That would reach its climax with Black Narcissus, but I can see it here, and it makes a cheap movie into something very interesting.

The Phantom Light isn’t one of Powell’s classics. It isn’t a great film. But it is a good film that shows a great artist finding his way.

Grumpy millionaire Jasper Whyte (Charley Grapewin) has given up hope of finding his granddaughter, who would be his sole heir, so on the night before the inheritance tax is set to rise, he tells his greedy relative and friends (Arthur Hohl, Lucien Littlefield, Regis Toomey, Hedda Hopper, Clarence Wilson, Rafaela Ottiano) that he will give them a million each on this night. However, immediately after, his granddaughter, Doris Waverly (Evalyn Knapp), appears at the door. As Jasper is getting to know her, another girl shows up claiming to be Doris (Mary Carlisle), this one accompanied by a stage magician (Wally Ford). And now both women are targets of a killer.

Old Dark House films are first cousins to Cozy Mysteries, but they aren’t the same thing. One Frightened Night is more mystery than horror. Yes, there’s a killer, but only the granddaughter, or anyone claiming to be her, is a potential victim. No one else is in danger. And the murderer is clearly one of the house guests. There’s no suggestion of a supernatural source or an escaped maniac. No one goes off to sleep and there’s not even an ongoing thunderstorm. Once there’s a murder, the police show up and for the rest of the film it’s interrogations and clue-finding. It still has plenty of the Old Dark House characteristics: the large house, the rich old man and his “will,” secret passageways, and screams. Plus there’s a bit more rushing about then in an average Cozy, but it’s quite a stretch to call it horror. Outside of classification, is that a problem? Well, yes. With the spooky elements so restrained, it needs a stronger detective/mystery story than it has to take up the slack.

The dialog is snappy, and the cast as a whole carries it off well. What keeps this film a step ahead of many of its peers is Charley Grapewin. He would soon jump into A-Pictures with The Petrified Forest and The Wizard of Oz, though he’d always be a character actor. Here he’s a curmudgeony fireball, with some real emotion between verbal attacks. He’s a more powerful actor than found in a majority of Poverty Row pictures.

When Sir Borotyn’s body is found, drained of all it’s blood, superstitious Dr. Doskil (Donald Meek) declares the cause of death to be a vampire attack, and the townspeople agree. Skeptical Police Inspector Neumann (Lionel Atwill) calls in Professor Zelen (Lionel Barrymore) who agrees with the doctor. Zelen fears that the new residents of the castle, Count Mora (Bela Lugosi) and his daughter Luna (Carol Borland), are the vampires and they are after Borotyn’s daughter (Elizabeth Allan). Baron Otto von Zinden (Jean Hersholt), the executor of the Borotyn estate, teams up with Newmann and Zelen to defeat the vampires.

Mark of the Vampire is one the the “almosts” of film history. It is so stylish, so funny, and so filled with brilliant work, that when it falls apart, it ends up disappointing almost everyone who watches it. Not that it could avoid that. Directed by Tod Browning, it is a remake of his own greatly hyped, and now lost, silent film, London After Midnight, staring Lon Chaney. In all probability, the later film is the better one, but it’s hard to stand in the shadow of a ghost.

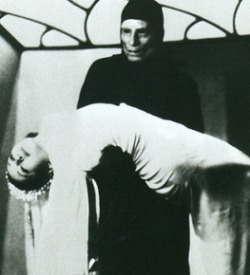

Browning, who had learned a few things about shooting talking pictures in the four years since he’d made Dracula, filled Mark of the Vampire with one great set piece after another. The vampires look better, stranger, and more menacing. Lugosi played this vampire as Dracula gone feral (it’s easy to see where the inspiration for Christopher Lee’s Dracula came from). Borland’s Luna is stunning, and defined the female vampire. It is said that Charles Addams created Morticia after seeing Borland’s performance. With atmosphere to spare, this may be the most beautiful of the horror films of the ’30s-’50s.

The cast is excellent, filled with genre staples. Lugosi and Borland are the standouts, but Meek, Atwill, Hersholt, and Allan all excel. For a change, Barrymore doesn’t annoy me, but there is a trick to his performance which ties into the structure of the movie. You see, this isn’t just another vampire film, but is a postmodern spoof. Yes, four years after Dracula and there was enough to make fun of in the vampire sub-genre, though Browning particularly rips at himself. The plot is very similar to his version of Dracula with Barrymore’s Professor Zelen a variant of Van Helsing, focusing on everything that was silly about the character the first time around. This is a movie where everyone, including the viewer, knows the vampire story, and it’s just a matter of seeing how Browning is going to twist things. And twist them he does. Many people who don’t like this film object to its postmodern nature, wanting the picture to be an improved retread of Dracula. In the end, it turns into something very different, and that makes it so much better.

But not all is well. There are two radical changes toward the end of the film, not one. The first is when we are let in on a character’s plan and the film shows itself to be something more than what it appeared to be. If that had been the end of the movie, I would rank this as one of the greats. Unfortunately, there is an additional segment dealing with hypnosis that makes most of what went on before it unimportant. I can’t fathom why Browning and script writers Guy Endore and Bernard Schubert would strip away the previous forty minutes of the film. With the hypnosis subplot, Mark of the Vampire becomes an elegant and amusing curiosity.

John Kendrick (Onslow Stevens), Louise Stone (Lois Wilson) and Robert Cornish (playing himself) are three happy college students out to change the world with their theory of bringing the dead back to life. At graduation, Kendrick excitedly tells his colleagues how he’s gotten them all jobs at a pharmaceutical company. The others object because a commercial firm can never share their lofty goals, but Kendrick is certain that their resources will complete the project faster, and abandons them. Kendrick becomes even more obsessed, and he also marries a socialite (Valerie Hobson) and has a child, though those aren’t important matters as we learn about the first only through a newspaper headline. As it turns out, Stone and Cornish were correct—as if that wasn’t really clear from the start—and the company wants him to break off his vital research to work on “hair growth brushes.” This disappointment is too much for him and he has a mental breakdown. He runs around announcing that he wants to bring the dead to life, which for some reason doesn’t go over well. Then his wife dies of…I don’t know…perhaps being poor… It isn’t explained. Perhaps she died of Valerie Hobson walking off this project in disgust; that makes sense anyway. His child is taken away by the state since Kendrick shows no signs of being able to take care of anything (how does he still have a house?), but the kid runs away and meets up with a bunch of escapees from an Our Gang comedy that all live in a club house. The kid’s much beloved dog is captured by the dog catcher and put to death. So now it’s up to Dr. Kendrick, with help from Dr. Robert Cornish—who is the greatest human being to ever walk the Earth; all praise to Robert Cornish—to bring the dog back to life in order to regain his son’s love.

As Life Returns was distributed by Universal, starred Onslow Stevens who was in House of Dracula, co-starred Valerie Hobson who was in both The Werewolf of London and Bride of Frankenstein, and is about a “mad scientist” bringing the dead to life, it has gotten grouped in with Universal Horror. It doesn’t belong. It also was banned in Britain, so it’s gained a mystique. It doesn’t deserve that either—the mystique that is; the banning is another matter.

This isn’t Universal horror. This is trash cinema of the lowest sort, trying and failing to exploit a recent headline. Produced by Scienart Pictures (its only film), not Universal, the news it was exploiting involved Robert Cornish, although perhaps “exploit” is the wrong word as it is more of a propaganda piece, or advertisement for Cornish.

In the early ‘30s Dr. Robert Cornish had theories on “bringing the dead back to life” which today we’d call reviving or using CPR. He wanted to work on humans, but this was frowned upon, so he got five dogs, suffocated them, and then immediately tried to revive them with adrenaline and rocking them on a “teeterboard.” It didn’t work well, but had some effect. Three died; the other two were brain damaged and blind, after which Cornish hid them away and claimed it was a success. He was fired from the UCLA because they weren’t idiots. So he decided to work from home on pigs, because nothing says sane and reasonable like killing pigs in your extra bedroom in order to bring them back to life. Of course killing animals in your home can get pricey and he wanted funding, so he tried to get some positive publicity with Life Returns. I don’t know if he approached the producers or they approached him. The idea was to build an emotional, fictional story around a recording of one of his dog experiments. So footage of the actual experiment is in the film (and as Britain isn’t keen on animal abuse in cinema, it was banned) and the movie starts with two different statements on how Cornish’s work is miraculous and important. No mention was made of him being a weirdo working at home.

Life Returns didn’t gain Cornish the popular acclaimed he desired, possibly because it’s a tedious film. He did pop back up in the news some years later when he wanted to bring a convicted child-murderer back to life after his execution. Needless to say, the authorities weren’t keen on this idea. That he couldn’t have done it didn’t stop him getting as much press as possible out of it.

It’s hard to express how horrible this movie is. At first I couldn’t imagine how they got Valerie Hobson to appear in this kind of trash, but I hadn’t realized she was only 17 at the time (or perhaps 16 during filming) and is only in it for a few minutes. Onslow Stevens didn’t have a shining career, but he rated better than this, so I assuming they just lied to him. Cornish gets top billing.

I can’t find a budget for Life Returns, but by the look of it, I figure it was in the hundreds. The setups are primitive with the camera generally sitting in one place and the result is ugly (though to be fair, no one has put any care into preserving this abomination). Stock footage is used which doesn’t match the shot footage (and I’m not only referring to the experiment, which does indeed match extremely poorly; in an early montage we see a college graduation which clearly is from a different source from the set-bound scene that follows). The movie starts (after a fade-out of Cornish’s face), for no reason I can determine, with stock footage of wheat and ploughing. I’m guessing they could get it for free.

There’s something gruesome about the dog resurrection scene, knowing that we’re not watching some kid’s pup that had been dead for hours brought back, but a dog that Conrish had just killed and then only partially restored. The “procedure” is intercut with shots of Onslow Stevens overacting, a group of medical scientists watching, and the child oozing about how swell his dad is. All of which makes it worse.

The dialog is exactly what you’d expect from a quickly written propaganda flick. Important moments flash by with a few words, and then we get long speeches, all culminating in the final:

“Dr. Cornish is the man of the hour; Dr. Stone and I are merely contributors to his fulfillment. “

(Kid: “Dad, You’re the swellest dad in the world”)

“Gentleman, what you’ve seen demonstrated is only a forerunner in the march of science. It’s promise to humanity has been answered today. The next step is in the hands of tomorrow.”

Life Returns isn’t horror, except for it’s connection to dog murder. It’s sometimes called science fiction and I suppose that fits since Cornish couldn’t do what is implied in the film. The best label for Life Returns is garbage.

Dr. Gogol (Peter Lorre), perhaps the greatest surgeon in France, is obsessed with goth actress Yvonne Orlac (Frances Drake). Her husband (Colin Clive), a concert pianist, has his hands mangled in a train wreck and although Yvonne is frightened by Gogol, goes to him to try and save her husband’s hands. That’s impossible, so Gogol transplants the hands of a murderous knife-thrower onto him.

The Hays office did its best to cut Mad Love off at the knees, but it could only manage to snip away the simple and straightforward. The subtext and metaphor are strong and give the film more power than most horror films of the time. Gogol is the repressed virgin, whose sexual need and self-doubt as a man drive him insane and to violence. Stephen Orlac had previously taken a route no more fulfilling, but far more social acceptable: he’s sexless, with any sexuality he has pumped into his hands and his art. When his hands are cut off, it is equivalent to castrating him, and with his outlet gone, he too slips into insanity, picking up phallic knives and sticking them wherever he can. Yvonne’s sexuality is all fake, a performance. She writhes on stage when the hot irons caress her skin, a sexual goddess, which fades away when she changes to street cloths. There’s plenty to play with in all that if you are of a mind to do so.

This first sound version (of at least 4 adaptations) of the far better titled novel, The Hands of Orlac, smartly switches the focus from Orlac to Dr. Gogol. The part was beefed up when Lorre was cast, hot off his German classic M and recently immigrated to escape the Nazis. And it’s Lorre who powers the film. He’s more impressive here than in M—a great actor who knew how to express insanity and abnormality sympathetically. I found myself rooting for him. But then he has the best character. Yvonne abuses his interest in her to get him to work on Stephen in his home, something he wouldn’t normally do. Stephen Orlac’s mix of weakness and drama creates a personality that is impossible to like, and Colin Clive is an actor prone to turn it up to twelve. His kind of histrionics works only when under control of a very peculiar kind of artist, such as James Whale. Karl Freund was not that kind of director. His genius lay in the look of film. He was the cinematographer on Metropolis, and while he could have easily functioned with a 3rd rate cinematographer, he instead had Gregg Toland working for him here, who would later shoot Wuthering Heights and Citizen Kane. It seems almost silly to point out that Mad Love looks incredible. Freund digs into his German expressionistic roots, giving us arches and strange angles and shadows that seem set to reach out and pull the lost humans into oblivion.

The conventional ending, which feels both hurried and tacked on, as well as Clive, and a reporter that is meant as comic relief but never quite makes it, drags Mad Love down, but there’s enough here to put it on a short list for any fan of classic horror.

Depressed, jealous, opium-addicted choirmaster John Jasper (Claude Rains) is obsessed by Rosa Bud (Heather Angel), who is the fiancée of his nephew, Edwin Drood’s (David Manners). She finds Jasper’s attentions creepy, though she keeps it to herself. Neville Landless (Douglass Montgomery) and his sister Helena (Valerie Hobson), of mixed racial heritage, come to town with Neville falling immediately for Rosa and Helena becoming Rosa’s roommate. Neville and Edwin come to blows over Rosa, but Neville’s sensitivity has an unexpected source: he doesn’t want to marry Rosa. And luckily for Neville, she doesn’t want to marry Edwin, and the two call off their engagement. Unfortunately, they don’t tell anyone, and when Jasper sees them in a goodbye embrace, he becomes murderous. Soon after, Edwin disappears and Neville is blamed. But who really killed Edwin… OK, we know. It’s really, really obvious. Really, as in they should of changed the title to Not a Mystery of Edwin Drood.

The 1930s are filled with non-horror films in horror clothing. Mystery of Edwin Drood is the most notorious of those. Made at Universal by their horror team, its stars, as well as bit players, also appeared in classic monster films: Rains in the Invisible Man, Manners in Dracula, Hobson in Bride of Frankenstein and Werewolf of London. Director Stuart Walker was also at the helm of Werewolf of London, and writer John L. Balderston had his pen in Dracula, Frankenstein, The Mummy, Bride of Frankenstein, and Dracula’s Daughter. Its sets were shared by horror films, including the crypt now more famous from Bride of Frankenstein. There’s a storm, an opium nightmare, and gothic touches throughout, and Universal sold it to TV as a horror film. All of that sets expectations, which was the intention. But it isn’t horror. It’s a stodgy costume drama with a few tense moments. It lacks the thrills of a horror picture and the depth and complexity it would need as pure drama.

Despite the title, there’s no mystery, though the source material has a kind of mystery. The Mystery of Edwin Drood was the final novel of Charles Dickens, unfinished at the time of his death. We’ll never know if Dickens planned the story to be a mystery; the film decides that is isn’t, naming the killer before there is a killing. Many Dickens fans believe that he intended Edwin to be secretly alive, but I don’t object to Universal choosing to go a different way, only that they didn’t do anything interesting.

While there’s little that is horribly wrong in Mystery of Edwin Drood, I find little that’s right. The sets are nice and it’s shot professionally, but Walker has no flair. It looks pretty, but the way the camera is used doesn’t say anything special, which would be fine if the plot or characters were stronger. Thus I call it professional, or even skilled, but not artistic. The actors all are a bit confused. The supporting cast camp it up. That’s not surprisingly based on what they are used to doing in Universal horror pictures and what is easy to fall into with Dickens’s dialog, but Walker can’t make use of it the way James Whale did in The Invisible Man and Bride of Frankenstein. They need to release built up tension or show the quirky nature of humanity. Instead, when set next to the more serious performances, they seem silly. Rains is one who takes his part seriously—too seriously; I rate him as one of the greatest film actors, so his being off the mark I lay at Walker’s feet. Manners was not a good actor, and based on this, I’d say the same of Montgomery, but Hobson was solid, though not here. Again, I look to Walker, though poor Hobson and Montgomery were forced to perform in ridiculous brown-face makeup that couldn’t have helped.

Though that leads to my confusion on if this is a progressive or regressive film. The makeup is atrocious, and Neville is violent and uncontrolled. But he’s also the hero, which makes me wonder how this got past the censors. The Breen office didn’t allow interracial relationships. Did half-Indian not count? But then the film also got away with opium use, so I’ll change my earlier statement: the film did something right in getting around the Production Code.

I think their mistake with Mystery of Edwin Drood was trying to play it both ways. Universal should have made a straight, Dickens, period piece, or they should have gone full in with horror. What they ended up with isn’t much good as either.

Forceful and obsessed Doctor Forti (Carlos Villarías ) carries out strange medical experiments in his home, aided by his weak-willed son, Pablo (Joaquín Busquets). Pablo wanted only to play the violin and marry Forti’s beautiful ward Angélica (Beatriz Ramos) but instead does what Forti commands. Both Pablo’s Aunt Doña Engracia (Natalia Ortiz) and the butler know that there’s something wrong with Forti, but they have no power to stop him. Forti summons Doctor Montes (Miguel Arenas), who brings along his son Luis (René Cardona), who is both a friend of Pablo’s and in love with Angélica, announcing that Pablo’s wedding will be delayed as the two are going to the mysterious Land of Pale Faces, deep in the jungle, to continue his research, and Pablo meekly agrees. Eight years pass, and Angélica has finally given up on Pablo, and agreed to marry Luis when she hears Pablo’s violin music and sees a masked face at her window. The next day they find that Forti has returned with a fanatically loyal servant (Abraham Galán), and are informed that Pablo is dead. Forti pressures Angélica to move back in with him, and he has strange plans for her involving marrying the dead, while Doña, the butler, Montes, and Luis fight to save her.

This is the pinnacle of horror filmmaking in 1930s Mexico. Writer-director Juan Bustillo Oro, who’d written El fantasma del convento (1934) and directed the horror-adjacent drama Dos monjes (1934), gets right what others could not. El misterio del rostro pálido looks great, with some reasonable camera work, but mostly because of the set design, which merges expressionism with Art Deco. It’s beautiful and conveys a mood of strange otherworldliness. The music reminds me of Universal’s monster films, and the costuming also hits the right notes with the masked pale man having everything necessary to be an icon. The plot is nothing special but workable, and an eerie feeling hangs over it all. And Bustillo manages to tone down Villarías’s (best know for Drácula) tendencies to play to the back rows such that I hardly recognized him.

But damn, is it slow. So slow. We never get to know any of these folks, or care about them, be we do get to hear them talk. Forti is a mad doctor, but he’s even more of a chatty one. Everything is discussed, talked around, and then brought up yet again. I wanted to put the whole thing on 2x speed. The problem is integrated into every part of the picture, but I’ll lay it on editing. There was a very good horror movie here, but it died in post-production.

The ending is disappointing, both anticlimactic and unsatisfying, as two characters do complete personality shifts in under three minutes, but I could only get so annoyed as I was too bored to get emotional.

El misterio del rostro pálido was released with no premier, little publicity, and to little notice. Bustillo’s later successes in more mainstream fare are all that kept this film in anyone’s mind. It should, and so easily could, have been much better, but just as people did in 1935, it’s fine to ignore it. If you are curious, come for the Art Deco-expressionism, and leave when you’ve gotten your fill of architecture.

Prof. James Houghland (Charles Hill Mailes) has invented a new technology for that newest of new products: the television. Multiple companies want his invention, and secretive people threaten him. During his demonstration, he is murdered. Nelson, the chief of police (Henry Mowbray) has many suspects, including Houghland’s assistant Dr. Arthur Perry (Bela Lugosi), medical experimentalist Dr. Henry Scofield (Huntley Gordon), Richard Grayson (George Meeker), and the two servants, Isabella – the Cook (Hattie McDaniel) and Ah Ling – The Houseboy (Allen Jung), and he is keeping them all close at hand until he finds the murderer.

In 1935, this was science fiction. Transmitting moving images from multiple locations around the world onto a large screen was something yet to happen. It would be nearly a decade before commercial television broadcasts were more than just a lark. Now the technological death ray of this film, and the “science” of determining who could be a killer by examining their brain… Yeah, those things haven’t happened yet, and the second was stupid at the time. So, this is science fiction—very slow and dim science fiction.

But no one watches this film based on that genre. With its name including the word “murder” and the presence of Bela Lugosi, Murder by Television is often classified as horror. How does it stack up as horror? Significantly worse than it does as a mystery or science fiction. It’s not tense or frightening, nor does it try to be either. It’s plodding, with each clue examined and discussed two or three times longer than necessary. As a procedural, it’s tedious.

The characters are mostly forgettable, though not the subservient, hysterical Black cook or the fortune-cookie quoting Asian house boy. Yes, he’s a “house boy.” When the white woman sees someone who looks like the dead man, she calmly tells the others that she’s seen something she can’t explain. When the cook sees the same thing, she comes screaming into the room, yelling “Oh’lordy Lordy!” and drops to her knees blubbering about ghosts. I’ve seen more racist portrayal, but Hattie McDaniel is usually a bit less embarrassing.

The only other actor to make a mark doesn’t make me cringe. Bela Lugosi doesn’t have much of a part to work with, but he’s charismatic enough that I didn’t mind most of the overly long discussions that he was a part of. Although even he couldn’t pull off the never-ending speech at the end, where there are long pauses as the camera frames one person, then the next, and then the next. Yes, I know they are all listening. Maybe you could show them while he’s talking instead of giving us a few words, then a couple second shot of each and every person in the room, and then a few more words, rinse and repeat.

Murder by Television isn’t terrible. It’s just not very interesting, and the basic filmmaking skill is lacking. This was made in 1935, when most of the industry was getting the hang of how to make films in the sound era. I’d have bet this was made in 1930 if I hadn’t seen the date. It’s primitive next to Dracula, which was made four years earlier. Lugosi isn’t enough of a reason to spend an hour with Murder by Television. Just watch Dracula again.

The first feature-length, talkie, version of Dickens’ story in which Ebenezer Scrooge (Sir Seymour Hicks) learns the meaning of Christmas from three spirits.

Quick Review: Yes, 1935 was a long time ago and many film techniques were not yet invented, but that is no excuse for dull acting and non-existent camera work. Nor does saying “it was the depression,” make up for poor execution. Those are explanations for this film’s failure, but noting them doesn’t make it any less of a failure. I might be able to ignore the invisible ghosts (Marley and the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come are not seen, and the Ghost of Christmas Past is just a blur) but the static camera work stays with me. Cameras need to move. Not a lot necessarily, but some. In Scrooge, the cameraman must have stepped out for a quick sandwich while filming.

Seymour Hicks plays Scrooge as if he he’s reading the lines for the first time (surprising for a man who had performed the part on stage for years). The rest of the cast are forgettable (well, Christmas Present isn’t, but it’s a performance I’d prefer to forget). As Dickens wrote a good story, I’d be forced to recommend this film if no others existed, but many others exist.