The Four Bennet Daughters (Dutch – 1961)

Pride and Prejudice (1967)

Pride and Prejudice (A&E – 1995)

Pride & Prejudice (2005)

Pride and Prejudice (BBC – 1980)

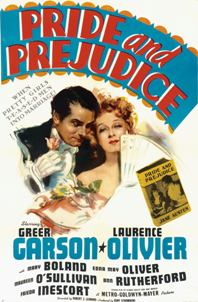

Pride and Prejudice (1940)

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016)

Pride and Prejudice: A Latter Day Comedy (2003)

Bride and Prejudice (2004)

Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001)

A classic novel by Jane Austen, Pride and Prejudice is the story of Lizzie, the brightest and second oldest of the five Bennet sisters. The Bennets are a caring family at the bottom rung of the upper class with a problem that is forever on Mrs. Bennet’s mind: how do you acquire suitable husbands for so many girls. Things look up when wealthy Mr. Bingley takes the nearby estate and shows an interest in the eldest girl, Jane. Unfortunately, he brings with him his much richer, but unpleasant friend, Darcy. Darcy is rude and haughty, and Lizzie finds him the most detestable man she has ever met. Her opinion is supported by Mr. Wickham, a handsome soldier that knows Darcy from the past. Darcy’s behavior devolves further when he breaks up Bingley and Jane because her family is unsuitable. Thus, it comes as a shock to Lizzie when Darcy professes his love for her, and asks for her hand. Of course she refuses, which comes as a shock to him. It all seems straightforward, but perhaps the prejudices of both Lizzie and Darcy have them viewing good people poorly and corrupt ones as noble. Additionally, it is possible, with the proper motivation, for people to change.

Pride and Prejudice, the book, is a romance, satire, and comedy. Adaptations tend to keep all three of those properties, though the percentages change. Every version wishes to be a romance first, cutting as little as possible and occasionally adding shots that might have shocked Austen. Both the satire and comedy are not treated as quite so holy. In a few cases, the comedy is dialed up, but it is more common to decrease both.

The biggest trick in adapting the book for the screen is that film is much more objective than literature. A novel is generally slanted by the point of view of the protagonist; unless the filmmaker takes elaborate steps (see anything by Davie Lynch), what you see on the screen represents reality. But Austen was particularly prone to masking reality. On the page, Darcy’s unpleasantness is filtered through Lizzie’s eyes, making it very plausible that he isn’t, as Lizzie sees him to be, the biggest jerk in the world. It is her prejudice at work. But on the screen, if Darcy looks like an ass, then he really IS an ass.

Pride and Prejudice (1940) – Greer Garson/Laurence Olivier

Anyone bothered by the changes from the novel in the versions I review below will enter a state of apoplexy with this one. That doesn’t mean it isn’t charming, just different.

The satire has faded away in the face of romance and humor. This is a frothy, funny take on the material, much in the style of the romantic comedies of the era. The advertisement suggested: Bachelors beware! Five gorgeous beauties are on a madcap manhunt! A bit misleading as the movie never enters the land of screwball comedy, but you are definitely working with a different tone.

Also in keeping with those times, the actresses are too old for their parts. No wonder Mrs. Bennet was panicking when she’s got an unmarried thirty-six-year-old daughter in the house. Wickham’s ability to talk a twenty-year-old into an illicit encounter also seems less scandalous.

Even age-challenged, Greer Garson makes a delightful Lizzie. Smart, sharp, and attractive, she’s more of an ideal 1940s woman than an 1820s one, but an ideal woman is an ideal woman, so let’s not get picky. Edmund Gwenn (Miracle on 34th Street) is a more than amiable Mr. Bennet and Mary Boland makes even Mrs. Bennet sympathetic. Melville Cooper (The Adventures of Robin Hood, The King’s Thief) takes on a defrocked Mr. Collins (the production code forbid disparaging men of the cloth) and simpers as only he can, and Edna May Oliver gives us the only version of Lady Catherine de Bourgh that I would like to meet. In the largest alteration of any character, Lady Catherine becomes a loving aunt to Darcy with sensibilities from another age.

As a romantic-comedy, the 1940 Pride and Prejudice works because of the changes to Darcy. Laurence Olivier does a fine job bringing him to life, but it’s the script that’s more important. It makes this by far the most pleasant Darcy. Yes, he’s pompous and arrogant, but in an easily forgivable way. He’s what you wish for in 1940s hero, but he has no connection to a man of the early 1800s. Watch this for a Golden Age rom-com, not for Jane Austen.

De vier dochters Bennet {aka The Four Bennet Daughters} (1961) – Lies Franken/Ramses Shaffy

Yet another non-English language version of Pride & Prejudice, this Dutch six-part mini-series was broadcast four years after the Italian one, but unlike it, is based on a BBC production in the ‘50s, taking it’s script and translating it (as no copies of the English script exist, I can’t say how much was altered in the translation. It’s no surprise that I can find little of Austen’s dialog once we swap languages, and then swap back in subtitles. For the most part, what’s said means the same as in the book; it just isn’t as nicely formed.

Yet another non-English language version of Pride & Prejudice, this Dutch six-part mini-series was broadcast four years after the Italian one, but unlike it, is based on a BBC production in the ‘50s, taking it’s script and translating it (as no copies of the English script exist, I can’t say how much was altered in the translation. It’s no surprise that I can find little of Austen’s dialog once we swap languages, and then swap back in subtitles. For the most part, what’s said means the same as in the book; it just isn’t as nicely formed.

As best as I can determine, the series was broadcast partly live, with extensive pre-shot scenes. This limited sets and camera angles, and allows for a few dialog mistakes. I’m sure they had reason for doing it live, but it doesn’t create an attractive version, with everything taking place on a few small sets.

As the title suggests, we’ve lost a daughter, merging Mary and Kitty. Mr. Bennet is mainly concerned with playing jokes on his family; the basis for that is in the book, but not to this degree. Mr. Collins has been toned down to the point that almost like him. I can believe both he and his wife will be happy in their marriage. I also feel sorry for him, as Lady Catherine forces him to cut down his prized beans because they are too lofty and he must know his place. I can’t come up with a reason why we needed a scene of Mr. Collins in despair, but we have one. Mr. Wickham has also undergone a change. Gone is the charismatic seducer, replaced by a rough thug.

Lizzy (the subtitles start with that spelling but later switch to “Lizzie”) has has more edge, being nearly as rude as Caroline Bingley. She’s bordering on unpleasant. The same cannot be said for Mr. Darcy, who is open and friendly (he is, however, unaware that others can overhear his private conversations from two feet away—remember, cramped sets). Darcy smiles frequently, laughs, and is generally pleasant. This is Fun Darcy, and Pride and Prejudice is a bit odd with so much less pride than normal for him. Lizzy has picked it all up. This is the only version of the story where I like Darcy more than Lizzy. The first proposal scene is bizarre, with everything explained and them departing as friends. The same events may take place, though sometimes combined, but it feels very different.

Darcy is also clearly obsessed with Lizzy from the start, and says so whenever possible. But then everything is clearer. Everyone is more direct, so direct that I’m surprised we don’t get a few murders. These are not folks who are concerned with proper etiquette or clearly speaking around a topic. When they’ve got something to say, they say it.

Each segment begins with a reading from one of the daughter’s diaries–Mostly Lizzy’s–to get you up to date on what’s happened in previous installments. But starting with the fourth, there is an additional, comical intro. These start odd, and get odder, giving us puppets in the sixth.

This is interesting as a curiosity. I can’t wholeheartedly recommend it, particularly at over 4 hours, but if you have been wondering what the story would be like with a all-heroic, all kindly Mr. Darcy, it could be worth your time.

Pride and Prejudice (1967) – Celia Bannerman/Lewis Fiander

Three previous TV adaptations are lost (I’ve heard that the hour long ’49 version exists, but cannot I cannot find it), leaving this the earliest existing English-language television version you are likely to be able to watch. Six episodes, at under 25 minutes each, makes this a short mini-series, though longer than the theatrical adaptations. It manages to hit most of the story points, though the details are whittled, yet it strikes me as more of a reflection of Pride and Prejudice than the real thing. The dialog approaches that of Jane Austen, and sometimes crosses it, but often runs far away. Have no fear if you find the book occasionally complex as all dialog has been simplified such that everything is obvious, and extra scenes are added to over-clarify. If it’s possible to spell things out, then they will be spelled out. Think of it as a child’s version—a competently made child’s version, but one none the less.

Three previous TV adaptations are lost (I’ve heard that the hour long ’49 version exists, but cannot I cannot find it), leaving this the earliest existing English-language television version you are likely to be able to watch. Six episodes, at under 25 minutes each, makes this a short mini-series, though longer than the theatrical adaptations. It manages to hit most of the story points, though the details are whittled, yet it strikes me as more of a reflection of Pride and Prejudice than the real thing. The dialog approaches that of Jane Austen, and sometimes crosses it, but often runs far away. Have no fear if you find the book occasionally complex as all dialog has been simplified such that everything is obvious, and extra scenes are added to over-clarify. If it’s possible to spell things out, then they will be spelled out. Think of it as a child’s version—a competently made child’s version, but one none the less.

While the first quarter follows the book reasonably well in plot, the emphasis is on Mrs. Bennet and the Bingley sisters. Caroline Bingley’s desire to return to London is of greater importance than anything dealing with Lizzie. Even in later sections, Miss Bingley gets an outsized amount of attention. Maybe that’s why Mary Bennet gets none. She’s missing; there are only four Bennet daughters.

Darcy is unrecognizable and variable in disposition. He’s more of a rom-com Darcy, a bit of a playboy, who smiles and smirks and loves word play. It makes him more likable in general, but it throws his stern moments into sharp relief, making him unhinged. But he’s not the worst Darcy. Lizzie also has her edges sanded down, and I find her a pleasant heroine.

The comedy is toned down; much is mildly amusing, but little is funny. Mr. Collins is often the funniest character, and that is true here. This is not my favorite portrayal, but it’s a good one.

The only cast member who I immediately recognized was Michael Gough, now more often known as Alfred Pennyworth in four Batman films, as Mr. Bennet. He makes an unusual Mr. Bennet, a bit young, but also effeminate and creepy. I can’t imagine this Lizzie feeling close to this Mr. Bennet. And I can’t figure why anyone would be attracted to this Wickham. He should never be dull.

This isn’t an unpleasant viewing experience, particularly as it doesn’t run too long. I don’t think anyone needs dumbed-down Austen, but for what it is, it isn’t bad.

Pride and Prejudice (BBC – 1980) – Elizabeth Garvie/David Rintoul

This is another miniseries, and due to its length, could be considered one of the most complete adaptations, but that depends on how you define complete. Certainly there is dialog which can only be found here and in the book. But there are also major scenes missing and lines relocated to unlikely locations. I suppose I should leave discussion of the “purity” of the material to the Janeites.

This is another miniseries, and due to its length, could be considered one of the most complete adaptations, but that depends on how you define complete. Certainly there is dialog which can only be found here and in the book. But there are also major scenes missing and lines relocated to unlikely locations. I suppose I should leave discussion of the “purity” of the material to the Janeites.

One very noticeable adjustment is to Lizzie. I suppose it was to clarify the title, so this Lizzie is prejudice about most everything and to a degree the novel would never approach. She immediately judges every person and situation, and is incorrect in almost every case. This makes her the least amiable Lizzie, but still the best thing about the series. Garvie is bright-eyed and attractive. She’s more of an “every woman” Lizzie then the exceptional one in other films and series.

Interestingly, while this Lizzie is less sympathetic, Mr. Collins is more. This makes him less funny than usual, though I did laugh when he showed off his dancing skills. But then, all of the characters are less enjoyable than I would like them to be and it is easy to find better renditions. The absurdity of the characters is highlighted, often going too far, making them unpleasant to watch. Mrs. Bennet and the three younger sisters can be hard to take if not deftly handled; in this case their obnoxious behavior (repeated again and again and again) made me long for the subtlety of a Jim Carey movie. Mr. Bennet is played as a harder man, showing no love for most of his family. He is occasionally cruel to them, but it is quite understandable, and I sympathized with his hiding in the library more than ever. Mr. Wickham is better than in the previous mini-series, but he still lacks the charm needed for the story to work. Even Jane’s sunny disposition is tedious. This is Pride and Prejudice with people you don’t like and will never want to meet. The few that aren’t horrible by their own traits are so by association. Each time Elizabeth shows respect or fondness for her family, friends, and Darcy, my estimation of her decreases.

As for it being a comedy, it is to the extent that it is unreal, always two steps away from how humans behave, but it is never actually funny. While the acting has been attacked by other critics as stilted, I can’t see that as a fair criticism. As with most comedies, realism is nudged to the side (if not thrown out all together). There is no reason why anyone should sound like an actual person. Also as a comedy, it can be excused for the lack of chemistry between its stars. If I was informed that Elizabeth Garvie and David Rintoul hated each other, and that there were several attempts by each to pluck out the other’s liver, perhaps with a more than normally dull spoon, then I’d be able to fathom their performances. This Lizzie holds Darcy in contempt from beginning to end, no matter what lines she is reciting. Rintoul brings the real humor to the show, although it is almost certainly accidental. I had thought of Darcy as a jerk in several adaptations, but never had I taken him to be a psycho-killer. This Darcy, with his inability to move his neck, constantly slit mouth, obsessed stare, and artificial gait, is just weird. I could plop him down in a horror movie as either an escaped mental patient that keeps eyeballs in a jar, or as an undead mummy only recently unwrapped, without any alteration. He’s a sick, unpleasant freak, and Lizzie even spitting out the words that she’s fond of him (no matter how much we don’t believe her) shows she’s under a demonic spell. In case that wasn’t clear, this does not work as a romance.

There is an attempt to deal with the subjective nature of the story by inserting very occasional narration, but it doesn’t fill in what’s necessary and instead repeats what we already know.

My comments do pain a negative picture (and I haven’t even mentioned the uninspired sets and fake military uniforms), but it is still Austen. Yes, it is slow and dry, but I found a good deal of pleasure in comparing it to both the superior and inferior adaptations. If you are a fan of the story, Garvie and company are worth one viewing.

Pride and Prejudice (1995) – Jennifer Ehle/Colin Firth

The 1995 adaptation, considered to be the definitive one by…well, just about everyone, isn’t a film at all, but a miniseries. Clocking in at just over five hours, it has the time to present the intricacies of the society and relationships, similarly to how it was done in the book. All main characters are fully fleshed out. Changes occur naturally, in steps that make sense and are clearly shown. That might make it sound leisurely, but it isn’t. The pace is swift and there are no slow moments.

The novel has been described as some combination of romance, comedy, and satire (obviously, there’s some overlap). The miniseries leans more toward romance. There is comedy, but it is primarily reserved for comic relief characters (particularly Mrs. Bennet, who is constantly complaining about her nerves, and Mr. Collins, a toady cousin who wants to marry Lizzie and seldom utters a line that doesn’t refer to the marvels of his aristocratic patron). Lizzie is brought to life by Jennifer Ehle, who accomplishes the impossible task of making women the world over, who always pictured themselves as Lizzie, see her as the beloved character. She is charming, and her eyes dance when she isn’t allowed to. Beautiful and witty, she is the personification of the intelligent costume-drama heroine. Colin Firth became a star due to his portrayal of Darcy, and a million women sighed in unison when he got wet, diving into a pond. I must admit, even I wanted these two to get together.

There is no skimping on the other relationships. Lizzie’s father is an important character, and here we see his love for Lizzie (and to a lesser extent, the rest of his family). It’s a pleasure to watch him as he comes to understand what has happened to his favorite daughter. Jane and Bingley are given time as well, enough to pull the viewers into their uneven romance.

Exquisite location shots (the U.S. simply doesn’t have mansions like these), appropriate costumes, and pleasant, non-intrusive music, all add to the ambiance. The camera work is adequate in showing off the stars and environments, and is better than expected for a television production.

This is the choice of purists, who want any film to match the novel. Well, they have nothing to complain about, and outside of Darcy being too much like Hitler’s second cousin in his first scene, I don’t either.

Pride & Prejudice (2005) – Keira Knightley/Matthew Macfadyen

I wonder if I would have reacted differently to the 2005

Pride and Prejudice if I hadn’t seen the miniseries first. I’m used to books being chopped up and compressed when they are turned into movies, and it doesn’t bother me (they are different media, so the stories need to be told differently). I am less accustomed to seeing a film condensed to make another film. But that is one of the primary impressions of this version. It is much like the ’95 series, but with substantial portions missing or shortened. As no subplots were removed, it’s no surprise that things are rushed: it is three hours shorter. There are also minor changes to the design. The Bennet’s house is no longer pristine, and the larger budget has allowed for some cliff-side romance shots, but none of that is significant. It is the loss of development time that matters.

So, we know what this version hasn’t got. What does it have? It has Keira Knightley. She owns every second of this film. Some critics were astonished at her performance, but that’s only because critics are a snooty lot, and don’t consider expertise in a pirate movie to count. Well, it does count, and as Lizzie, she’s now proved it to all. Knightley sparkles throughout. It doesn’t hurt that the actress is the same age as the character, but more important is the life, intelligence, and joy that she brings to the part. You care about all the events in the film, not because of their thorough development, but simply because Lizzie—this Lizzie—does. Watching the miniseries, you understand how someone could love Lizzie. In this film, it is you who will love her.

Is this version all about the star? All of the other actors are good (some, such as Rosamund Pike as Jane, and Donald Sutherland in the much reduced part of Mr. Bennet, are superb), the sets and locations are beautiful, the dances are energetic, and the music is pleasing. But yes, in the end, it is all about the star. And it is enough.

Well, perhaps not for everyone. While most people were thrilled with this version, one group was upset: the Janeites. These are fanatical Austen fans who want no deviation from the book, nor any changes from how they saw it in their minds. In the case of Keira Knightley’s Pride and Prejudice, they were dismayed that the Bennet’s don’t do more house cleaning, that when Darcey walks down the road, it is foggy and his coat flaps in the wind, and, most of all, that Darcey and Lizzie almost, but still do not, kiss. This is too gothic for their tastes (God help them should they ever see a vampire film; the gothic texture would cause them to explode) and smacks too much of romance. The trivial nature of these elements doesn’t matter to them. I like to think of these people as crazy, because it’s convenient to have neat categories for people, and because that way I can look at them with pity instead of distain. Pity’s nicer.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2016) – Lily James/Sam Riley

The first in the recent run of literary classics/horror mashups, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies made it to the screen a bit slower than Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter, which is just as well, since that attempt didn’t work out. What is surprising about it is how the basic story is straight Austin. It’s still bright Elizabeth, beautiful Jane, and their three silly sisters, trying to get by as their mother goes overboard trying to get them husbands. Mr. Bannet is still loving but would rather keep to himself. Pleasant Mr. Bingley shows up with his rude friend Darcy, as does Collins who’s again looking for a Bennet wife and drooling over his benefactor Lady Catherine. It’s the whole story, and if they pulled the zombies and dialed back Lizzie’s modern sensibilities, this could be a normal, and pretty solid version of Pride and Prejudice. Lily James is a fine Lizzie and the rest of the cast fulfill their rolls excellently, except for Sam Riley’s Darcy. He lacks the charm and depth needed, but he’s not the worst cinematic Darcy.

Combined with that, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies offers a fun zombie story with some fabulous world building. That allows for some fantastic scenes of Regency women in layered frocks pulling their multiple weapons and going full Resident Evil on the undead. So it is fun, twisted action along with Austin’s words. It sounds great.

But it isn’t great. The problem is right there in its success. Pride and Prejudice’s story not only fills up a movie, it requires that much time at a minimum. Previous film versions have felt too short. Now add in a zombie story complicated enough to fill an entire film on its own and we’ve got a time problem. Everything is way too rushed. We barely get to know the main characters. Forget about any of the secondary folks. At times this is less of a film then an overview.

The film needed to figure out what it wanted to be. If it was Austin, with zombies, then it needed at least another hour—I’d recommend making it a ten episode series. Jane seems great. Give me time to get to know her. Give me time to get to know the entire Bennet clan. Matt Smith appears funny yet affable as Parson Collins. Let’s have another thirty minutes with him. Lena Headey’s Lady Catherine was barely onscreen while I could have spent another hour just with her. As for Lizzie and Darcy—for there to be any chance of me caring about that relationship, wanting it to work, I needed to see him slowly revealed (or changed) into a man worthy of Lizzie and needed to see her broaden her views of the world. And then delve into that zombie plot a bit more.

If it just wanted to be a cute zombie story set in Austin-land, then pull way back on the Austin. Give us zombie slaughter that just happens to have leads named Elizabeth and Darcy who exist in a faux-Regency setting.

There’s enough in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies for me to recommend it, but it is a mild recommendation aimed at people already fans of Austin’s (but not purists) and already fans of zombies, who think the title is funny.

If costume dramas aren’t your thing, Austen has been updated for the new millennia, with three “hip” renditions in four years. That’s got to be a record.

Pride and Prejudice: A Latter Day Comedy (2003) – Kam Heskin

If you’ve seen

Clueless, and know that it is an adaptation of Austen’s

Emma, then you’ll know what the filmmakers had in mind when Elizabeth and Darcy (that’s Will Darcy) are transplanted to a Utah college town. Mom and Dad Bennet are gone, and Elizabeth’s four sisters are now her roommates. Darcy is a partner in a publishing firm, and stuffy, middle-aged pastor Collins has become stuffy, young, LDS (Latter Day Saints) missionary Collins. The comedy aspects of the story are given priority, and a rock beat backs up many of the scenes.

Not surprisingly, there are a few rough edges in the transition to current times. The story doesn’t make much sense in modern America, where women have options, a sense of decorum and the necessity for a good reputation do not strangle behavior, and marriage is not an absolute necessity. So, either the story has to be changed, or you’ve got to find a culture with a very conservative set of values. They did both. The characters are Mormons, which helps elevate the importance of virginity and marriage, but not enough to make it all sensible. Wickham’s plot has been altered to try and bring it into this century, but it doesn’t work. The emotion is missing.

While the connection to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints is purely cultural (there’s no preaching), and essential to explain the concerns of the character, strangely, the distributors of the DVD played it down. The title has been changed, removing “A Latter Day Comedy,” and a few lines have been cut or re-dubbed. This is the work of the brain dead. Removing the name of the church that everyone belongs to does not make the film more accessible, just inexplicable.

Kam Heskin is a likable Elizabeth, and most of the other actors are reasonable for a low-budget picture, but the film never jells. There is no sexual tension between the leads, the ending is forced, and worst of all, it isn’t funny. The jokes aren’t necessarily bad, but the timing is off. It’s part delivery, part editing, and part directing, but however you assign blame, there isn’t a laugh in sight. Elizabeth and Jane’s PMS ice-cream pig-out should have been funny, but it drags. There’s even a montage (yes, a montage, and it doesn’t even deal with martial arts training), which is a sign that the director and writers were lost with the material. It isn’t the plot that makes the novel a classic, but the language. Austen wrote excellent dialog and it’s not here. No one connected to this project was up to the task of replacing Austen.

Bride and Prejudice (2004) – Aishwarya Rai

The Bennets go Bollywood (well, faux Bollywood as this movie was produced in the West), with bright colors, singing, and dancing, but it’s a fairly straight rendition of the story from the novel. The advantage of the modern Indian setting is that the important old-style English sensibilities (marriage is vital, status is paramount, etc.) are still in place. The disadvantage? Well, once again we don’t get Austen’s language (except in rare instances), and the replacement is mediocre.

As for that singing and dancing, if you are a fan of Bollywood films, and don’t mind musical numbers that do not advance the story and are often at odds with the tone of the surrounding drama, you may find them tolerable. But probably not, since the songs very from not-too-bad to atrocious. If you haven’t acquired the taste for Bollywood, you’re in for a rough time.

Aishwarya Rai, a former Miss World, has no problem being beautiful. As Lalita Bakshi, the renamed Elizabeth, she doesn’t overwhelm with her acting chops, nor does she muck up the works. Unfortunately, she has no chemistry with Martin Henderson, whose William Darcy isn’t as much of a jerk at the film’s opening as his other incarnations, but also lacks the fire. He’s a milquetoast Darcy. The unfortunate actors are given little help by a script that requires them to argue about Indian culture, the problems with tourism, and the destruction of true India caused by the building of hotels. Ummmmm. Sure.

There’s fun to be had, and no one could complain that this isn’t bright and shiny entertainment, but it’s also no more than ankle deep. Think of it as Austen with some of the charm, but none of the soul. It would be a great extra on the DVDs of the Ehle/Firth or Knightley versions.

Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001) – Renée Zellweger/Colin Firth/Hugh Grant

If you are having trouble fitting

Pride and Prejudice into a modern setting, why bother forcing it? Just take what you like. That’s the philosophy behind

Bridget Jones’s Diary, which isn’t a version of Austen’s work, but merely inspired by it, and then only when convenient.

Bridget has the kindness and wit of Lizzie, but not her intelligence (yes, wit doesn’t equal intelligence). Where Lizzie was a special girl, Bridget is every girl. Mark Darcy is Darcy, with little alteration, and is even played by Colin Firth, who changes nothing from his previous version. Daniel Cleaver is a more charming version of Wickham, who is just as slimy, but somehow more loveable. His feud with Darcy has completely changed, as has the “foul deed” that makes the heroine change her opinion of him. Mr. Jones is more befuddled than Mr. Bennet, but he has the same warm relationship with his daughter. And Bridget’s mother is trying to get her married off in embarrassing ways. More of the characters could be mapped onto counterparts in Pride and Prejudice, but the fit becomes awkward.

People can argue about how well this works as Pride and Prejudice, (and they do, with many Janeites offended by the language and sex—they are really silly people), but as Bridget Jones’s Diary, it works brilliantly. There’s just enough romance and plenty of humor. Renée Zellweger transforms herself into a pleasingly plump, London, thirty-something with the insecurities of a generation setting on her shoulders; without prior knowledge, you’d never guess that she spends most of her time as a Texan stick-insect (to borrow a term from the movie). Bridget fears almost everything, but also enjoys her vices. She smokes, drinks, eats chocolate, and runs off to the country for anal sex with her boss. She’s looking for love, self-respect, and a good time, and in the end, she gets all three. But first she has to do everything just a little wrong (and a few things monumentally wrong). Most of it is funny (particularly whenever Hugh Grant shows up), but it wouldn’t work if you didn’t care so much for Bridget. It also has the finest fight between two forty-year-old men ever filmed (the average forty-year-old does not know martial arts, boxing, or any other combat skill to save him from looking as silly as a kindergartener when it comes to fisticuffs ).

You’d think after all those—plus viewings of Sense and Sensibility and Emma—I’d be all Austened-out. But I could repeat (most of them) tomorrow. Happily, they are out on disk, so I can. And guys, these aren’t popcorn movies. Get out the champagne and strawberries. Trust me.

Yet another non-English language version of Pride & Prejudice, this Dutch six-part mini-series was broadcast four years after the Italian one, but unlike it, is based on a BBC production in the ‘50s, taking it’s script and translating it (as no copies of the English script exist, I can’t say how much was altered in the translation. It’s no surprise that I can find little of Austen’s dialog once we swap languages, and then swap back in subtitles. For the most part, what’s said means the same as in the book; it just isn’t as nicely formed.

Yet another non-English language version of Pride & Prejudice, this Dutch six-part mini-series was broadcast four years after the Italian one, but unlike it, is based on a BBC production in the ‘50s, taking it’s script and translating it (as no copies of the English script exist, I can’t say how much was altered in the translation. It’s no surprise that I can find little of Austen’s dialog once we swap languages, and then swap back in subtitles. For the most part, what’s said means the same as in the book; it just isn’t as nicely formed. Three previous TV adaptations are lost (I’ve heard that the hour long ’49 version exists, but cannot I cannot find it), leaving this the earliest existing English-language television version you are likely to be able to watch. Six episodes, at under 25 minutes each, makes this a short mini-series, though longer than the theatrical adaptations. It manages to hit most of the story points, though the details are whittled, yet it strikes me as more of a reflection of Pride and Prejudice than the real thing. The dialog approaches that of Jane Austen, and sometimes crosses it, but often runs far away. Have no fear if you find the book occasionally complex as all dialog has been simplified such that everything is obvious, and extra scenes are added to over-clarify. If it’s possible to spell things out, then they will be spelled out. Think of it as a child’s version—a competently made child’s version, but one none the less.

Three previous TV adaptations are lost (I’ve heard that the hour long ’49 version exists, but cannot I cannot find it), leaving this the earliest existing English-language television version you are likely to be able to watch. Six episodes, at under 25 minutes each, makes this a short mini-series, though longer than the theatrical adaptations. It manages to hit most of the story points, though the details are whittled, yet it strikes me as more of a reflection of Pride and Prejudice than the real thing. The dialog approaches that of Jane Austen, and sometimes crosses it, but often runs far away. Have no fear if you find the book occasionally complex as all dialog has been simplified such that everything is obvious, and extra scenes are added to over-clarify. If it’s possible to spell things out, then they will be spelled out. Think of it as a child’s version—a competently made child’s version, but one none the less. This is another miniseries, and due to its length, could be considered one of the most complete adaptations, but that depends on how you define complete. Certainly there is dialog which can only be found here and in the book. But there are also major scenes missing and lines relocated to unlikely locations. I suppose I should leave discussion of the “purity” of the material to the Janeites.

This is another miniseries, and due to its length, could be considered one of the most complete adaptations, but that depends on how you define complete. Certainly there is dialog which can only be found here and in the book. But there are also major scenes missing and lines relocated to unlikely locations. I suppose I should leave discussion of the “purity” of the material to the Janeites.

Other comparisons turn out better for The Sea Hawk. The early sea battle is spectacular, far surpassing what Captain Bloodhad to offer. And there is the music. This is Korngold at his finest. It is stirring. After listening for a few minutes, I wanted to go sink some Spanish ships myself, and I’m pretty much a pacifist.

Other comparisons turn out better for The Sea Hawk. The early sea battle is spectacular, far surpassing what Captain Bloodhad to offer. And there is the music. This is Korngold at his finest. It is stirring. After listening for a few minutes, I wanted to go sink some Spanish ships myself, and I’m pretty much a pacifist.